One hundred years ago, the SENĆOŦEN, or Saanich, language enjoyed a healthy vitality among the Indigenous W̱SÁNEC people of southwest British Columbia and south Vancouver Island.

In 2014, 18 years after the last residential school in Canada closed, only six people were known to be native speakers of the language.

“Language is our birthright,” says Renée Sampson, a SENĆOŦEN speaker, in an article published by Focus Magazine. “But it was deliberately taken away from us by the residential schools.”

Keeping an Indigenous language preserved is a great challenge that requires more than just a grant from the government. This year’s federal budget dedicates $5 million to preserve Indigenous languages over the next year, and the First Nations Cultural Council in British Columbia has contributed an average of $1 million a year since 1990. However, the Cultural Council estimates that $20 million is needed to document languages in British Columbia alone. Additionally, all aspects of Indigenous communities — including housing, elder care, and education — need to be vibrant to allow a successful revitalization, and not all receive adequate funding.

Lenore Grenoble, a University of Chicago linguist, says that “if you really want to revitalize a language, it takes a long time and a lot of commitment. If you need to learn the language from scratch and you’re an adult, it’s hard work. Think of how hard it is for an English speaker to really learn Spanish.”

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission report’s Calls to Action reinforce the Canadian government’s responsibility in keeping Indigenous languages alive. However, the Commission does not lay down a precise guideline for how preservation should occur.

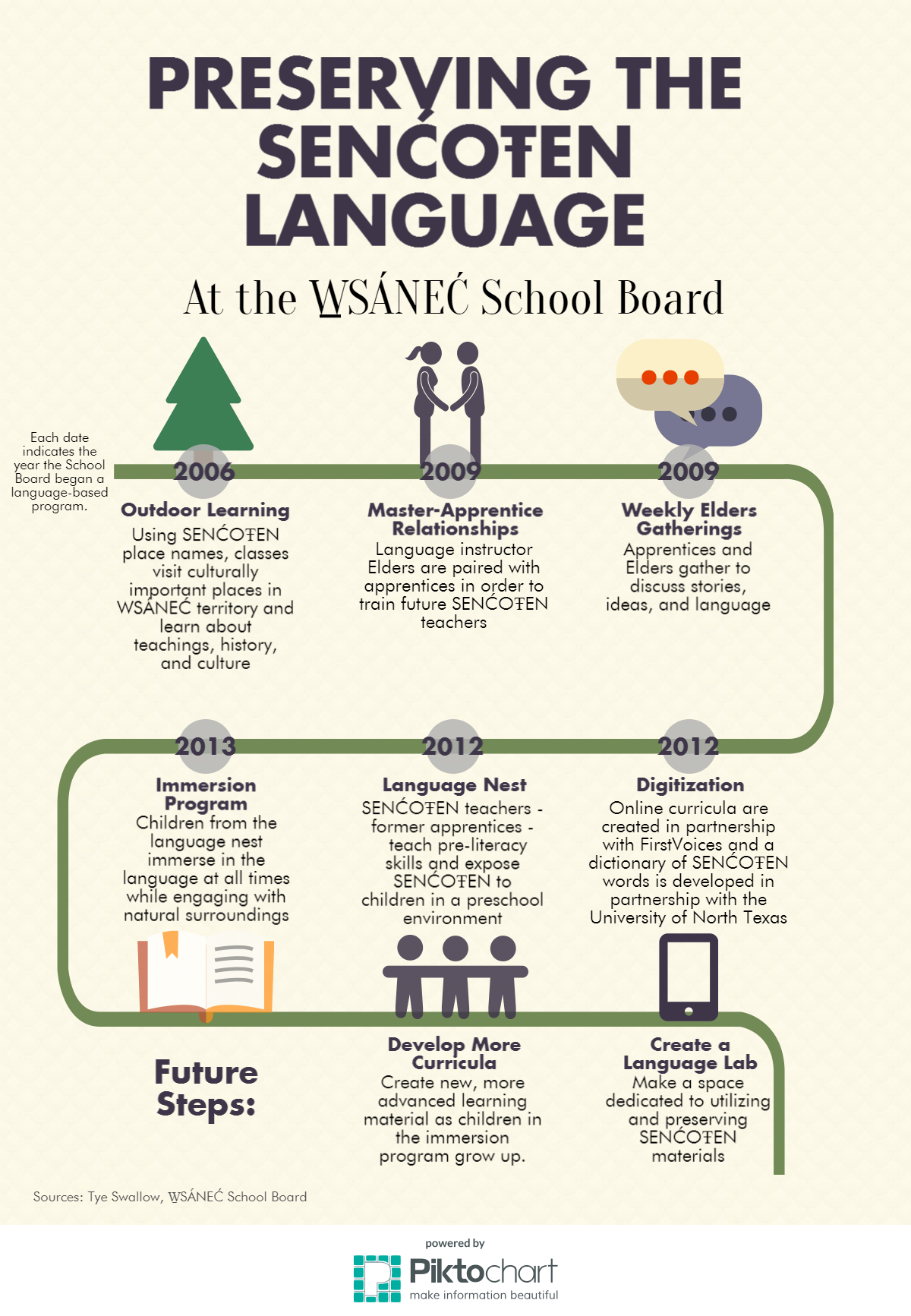

On the other hand, when the W̱SÁNEC School Board in south Vancouver Island established the SȾÁ,SEN TŦE SENĆOŦEN apprenticeship program, they knew that deliberate procedure is key to a language’s successful preservation.

The two-month program was created in 2009, lasting until 2012. Beginning with six people, each enrolled in a SENĆOŦEN education degree at the University of Victoria, a total of 16 apprentices were trained by fluent elders to gain proficiency in the language, the goal being to be able to subsequently teach children the language in an immersion environment.

Tye Swallow, a W̱SÁNEC School Board facilitator of language revitalization, says that heavy exposure is needed for successful revitalization. “One of the things I’ve become aware of is that communities all over the world have this notion that by having kids exposed to language for thirty minutes a day, it somehow keeps it alive. That’s one of the downfalls we’ve had.”

“A successful immersion program needs to be sustainable. We have a 25-, 30-year vision.”

Now, the apprentices use the skills learned in the program to teach SENĆOŦEN to others. Each year, they develop a higher-level curriculum for children enrolled in the SENĆOŦEN Survival Immersion Program. This year is the debut of the grade-three curriculum.

Other efforts by the School Board to preserve the language include outdoor W̱SÁNEC nature and culture classes, digitization of the language, and plans to create an interactive lab dedicated to SENĆOŦEN resources. Swallow says that the hope for the lab is for it to “house all of the old stories we have, the old uses of the language written by the speakers of the day.”

The School Board also strongly encourages parents to become SENĆOŦEN learners in order to involve themselves in their children’s education. In their guidebook for parents, they say that “learning your language with your child is a beautiful thing.”

Indigenous languages can have powerful effects for not only Indigenous communities, but the broader population as well.

PENÁC, a SENĆOŦEN speaker, said to Focus Magazine that “Our words tell us how to behave through the values associated with them. That’s why it isn’t easy to translate into English — those values get lost.”

The University of Victoria published a report in 2007 saying that “youth suicide rates effectively dropped to zero in those few communities in which at least half the band members reported a conversational knowledge of their own ‘native’ language.” In comparison, “those bands in which less than half of the members reported conversational knowledge suicide rates were six times greater.”

Evidence also shows that, even though revitalization costs money in the short term, it saves money in the long run.

“In general we find a high correlation between other indicators of social problems – high depression, suicide and alcoholism rates, high unemployment, crime, and so on – and loss of language,” Grenoble says. The money spent dealing with social issues typically costs more than preservation. For instance, StatsCan says that the average cost of a prisoner in a federal prison from 2013-2014, per year, was $108,770. As such, if the Canadian government were to double its $5 million budget for language preservation, they would actually make a profit if only 46 fewer Indigenous people were jailed as a result.

Swallow says that the revitalization of the SENĆOŦEN language has been very successful so far. “I’m so honoured and thankful, I’m privileged and humbled every time I get to do it. We have a lot of people that are very supportive of the program and the school boards.”

“The parents are quite tickled when they see their young children speaking the language. It’s taken on new life.”