When Lisa* graduated from teacher’s college to become a social studies teacher she wanted to teach her students about Indigenous issues, but even as a new graduate she feels inherently uncomfortable broaching Indigenous content with her students.

When Lisa* graduated from teacher’s college to become a social studies teacher she wanted to teach her students about Indigenous issues, but even as a new graduate she feels inherently uncomfortable broaching Indigenous content with her students.

In the duration of Lisa’s professional training, only one week was allotted to explore hundreds of years of Aboriginal histories, cultures and perspectives. Time that she said didn’t come close to deepening her own knowledge of Indigenous content, let alone prepare her to carry that knowledge forward into a classroom of students.

“I think if we had taken the time to look into the curriculum, I would have felt better teaching it in the classroom,” she said. She added that her one week crash course didn’t include coverage of residential schools or discussions of Canada’s colonial legacy.

Lisa left teacher’s college with the task of introducing her students to Indigenous content in a respectful and robust way yet was given very few resources and experiences that could prepare her to do so.

“It was a brand new curriculum that year, they had just released it and then it was given to me to teach. Even my mentor had never taught the material before. I guess my biggest worry was how I would be able to engage the class with this content in an appropriate way.”

This problem is not a new one. Although curriculum surrounding Indigenous histories, cultures and perspectives does exist, the depth of its application in the classroom depends entirely on the comfort level of the teachers delivering it.

Educational research organization, People for Education, conducts annual surveys of Ontario’s teachers to gauge what subject matter educators have the least comfort exploring within their classrooms.

Executive director of People for Education, Annie Kidder, says that despite the province’s efforts to enrich curricular content on Indigenous topics there is a troubling gap between educational policy and the reality on the ground.

“You can have curriculum that says this is mandatory; it’s there in name, but its application depends on our teachers’ level of comfort teaching or understanding it,” she said.“Our research into what subject matter teachers have the least level of comfort indicates that Indigenous perspectives, cultures, histories are areas where they consistently report not having that comfort.”

A provincial problem

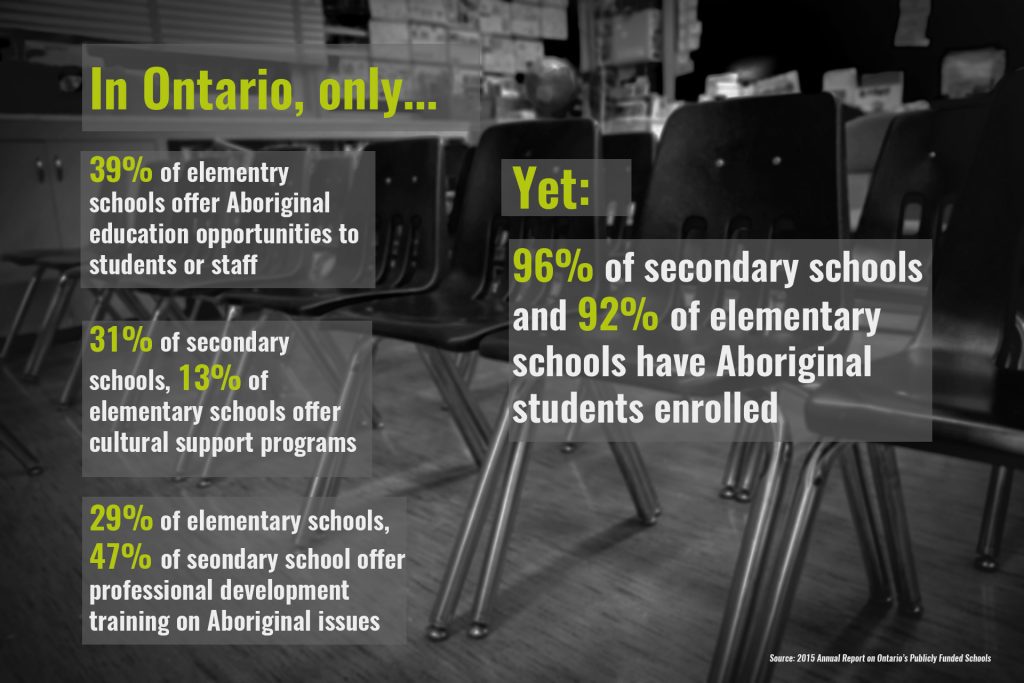

Despite this identifiable gap, the latest survey data conducted by People for Education indicates that only 47 per cent of secondary and 29 per cent of elementary schools offer professional development training and support for teaching staff surrounding Indigenous education issues.

When translated into the reality of teaching, this statistics mean that many teachers, like Lisa, are left to navigate Indigenous curriculum on their own.

“I think the thing now, is that maybe teachers are afraid to teach that unit because they don’t know too much about it,” said Lisa.“There are so many topics out there that are so sensitive, in terms of social justice issues, but you need to talk about them and you need to bring them out. I think that was my biggest struggle.”

Similar research into teachers’ roles in the delivery of Aboriginal education was also conducted with sights set specifically on the Toronto District School Board.

In 2010, York University professor Susan Dion and a team of researchers released Decolonizing Our Schools, a report revealing that teachers’ own discomfort and anxiety when it comes to teaching Aboriginal content was a sizeable barrier to its application in the classroom.

The study involved in-depth interviews with a mix of teachers from across the Toronto District School Board. Many participants reported an apprehension toward teaching Indigenous content born from feeling under-prepared, under-resourced and lacking in the appropriate time and support to present content to students.

Many teachers expressed concerns over misrepresenting Aboriginal cultures through their teaching practices. Some even voiced their fears of being judged for mishandling Aboriginal content or unknowingly participating in cultural appropriation of Indigenous cultural practices.

Another common response from teachers and principals was that without a large number of Indigenous students in their classrooms, Aboriginal education is ultimately unnecessary within their schools.

For Julia Candlish, director of education for the Chiefs of Ontario, it is important for educators to realize that this discomfort translates into a wide spread problem that isn’t just felt by students and peoples within Indigenous communities.

“All teachers need to include all of these components when they’re teaching their classes,” she said.“This is all part of the reconciliation and educating the general public about the history, the social concerns, the residential schools, the ’60s scoop, and including all of that information for all students. That discomfort should not be holding anyone back from teaching these components within the curriculum.”

The crux of the problem is not a lack of content, said Candlish, it’s the lack of confidence in the educators who are meant to deliver it.

“Teachers have lots of First Nations content that they could inject into the curriculum but they’re not comfortable utilizing it,” she said. “That means that the teachers need training – they need to be trained in order to be useful and teach the content.”

Dr. Suzanne Stewart, special advisor to the Dean of Education at OISE, explains that in order to foster reconciliation through education there needs to be a ideological shift surrounding the way society understands the blended histories that make up Canada’s past.

Infusing Indigenous perspectives into classrooms and curriculum is the first necessary step to propelling this understanding in the right direction.

“It’s about normalizing and explaining to people that we’re not teaching Indigenous history, we’re teaching Canadian history. We’re seeking to have students and society understand that we’re all in position and relation to Indigenous lands and Indigenous peoples. That it’s part of the Canadian context,” said Stewart.

Working Toward Re-education

In response to these problems, the TDSB’s Aboriginal Education Centre is working to bridge this knowledge gap.

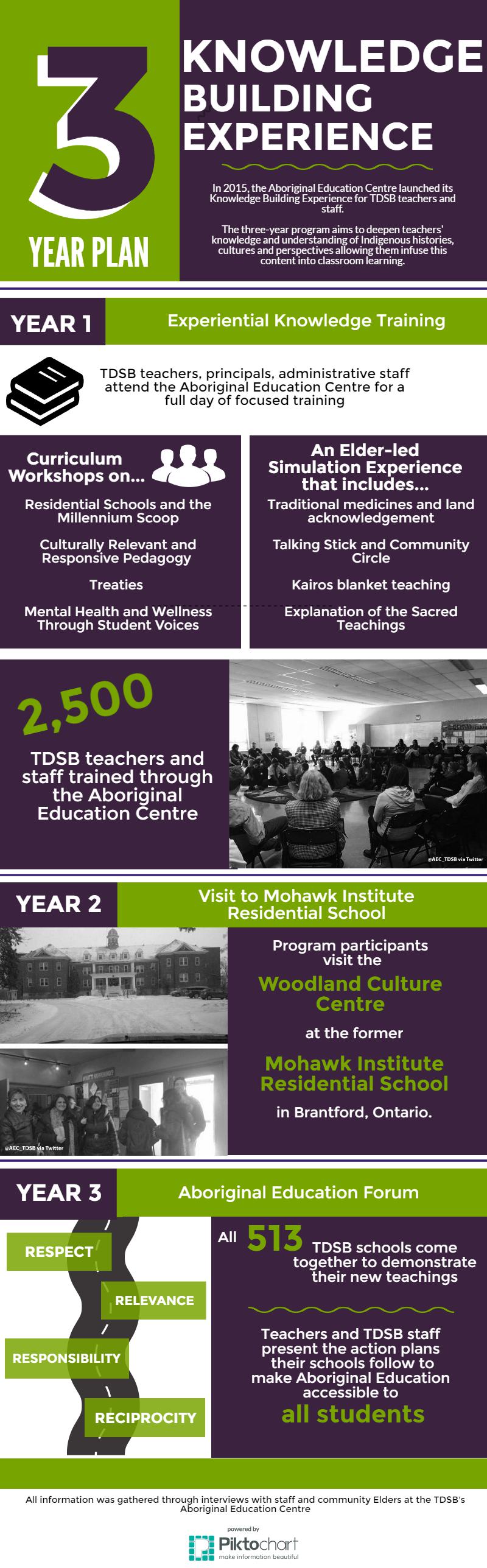

In 2015, the Aboriginal Education Centre launched its Knowledge Building Experience Program, aiming to enrich and deepen knowledge and understanding of Indigenous culture and issues for TDSB teachers and staff.

Co-ordinating principal, Barbara-Ann Felschow, said the program embodies entirely new strategies to reach all teachers and staff in a way that highlights both the accessibility of Indigenous education issues and its importance as a pillar of education for all students and teachers.

“Since 2006, this team has engaged in a number of initiatives to create and enhance understanding and knowledge, however it always seemed to be a hit or miss scenario that lacked intentionality,” she said. “This program’s three-year design evolved from conversations within the team that said there has to be intentionality through a framed way of engaging with every school and every teacher within this large system.”

The program organizes participants according to existing groupings of schools, or “school families,” in the TDSB. The goal is to reinforce communities of knowledge support between teachers and the team at the Aboriginal Education Centre.

The program organizes participants according to existing groupings of schools, or “school families,” in the TDSB. The goal is to reinforce communities of knowledge support between teachers and the team at the Aboriginal Education Centre.

“The idea was that as a family, your experience and your exposure is not just with a classroom teacher – it’s with everyone that has a connection to that school community,” said Felschow.

The mandatory training involves in-depth workshops on residential schools and the ’60s Scoop, culturally relative and responsive teaching practices, land-based and status treaties as well as mental health and wellness training explored through student experience.

But, the training goes far beyond seminar discussions and resource packages.

Participants also work along side community Elders and Traditional Knowledge Keepers through what Felschow calls simulation experiences. The simulations are based on experiential knowledge practices and take participants through narratives of cultural genocide, residential schools and marginalization through an Indigenous lens.

Joanne Dallaire is an Elder and counsellor working within the program. Her role is to help program participants navigate their anxiety toward Aboriginal education in a productive way that allows them to understand where this discomfort comes from, and ultimately, how to move past it. She describes the Knowledge Building Experience as a not only a process of re-education, but one of healing for all participants involved.

The program allows teachers to develop relationships with community members, said Dallaire, which gives them the opportunity to make personal connections with the material they are meant to teach.

For Dallaire, the program’s greatest strength is its ability to bring participants together through human experience.

“There are a lot of similarities in the human story,” she said.“I think that’s one of the things that the training exercise does is it brings you up to that human level and places these histories and cultures in something that everyone can relate to and respect.”

After concluding its first successful year, the Aboriginal Education Centre trained 2,500 teachers, administrators, principals and superintendents. The hope is that unlike previous attempts, this program will successfully accomplish lasting change surrounding teachers’ attitudes toward Indigenous education.

“It’s a journey, and it would be misrepresentation to say we’ve arrived because if we say we’ve arrived we wouldn’t strive to keep moving forward,” said Felschow.“We’re not there yet, but we have a strong desire and a passionate commitment to getting there.”

For Dallaire, the program seems to be a crucial step in a promising direction.

“This experience is one of the most powerful and most effective I have witnessed. I really think that there are ways that teachers can adapt this program to fit the emotional intelligence of little ones, intermediates and high school students,” she said.

She added, “You just have to find that human connection.”