Get out a glass. Turn on the tap. Drink. It’s a simple ritual for most Canadians. But for the nearly half million residents living on First Nation reserves, their water may be laced with mercury, arsenic, uranium.

More than 100 First Nations communities are currently affected by Drinking Water Advisories (DWAs) in this country. A growing number of critics are taking note of what’s been deemed “Third World” conditions in a nation renowned for high living standards and pristine waters. To address this paradox, the Liberal government has promised to end all DWAs by 2021.

Elder Josephine Mandamin Photo: Ayse Gursoz

“I’ve been taught not to feel sorry for myself, not to feel any hurt.”listen from Water Journey

But a group of Indigenous grandmothers can’t wait that long. Armed with copper pails and long skirts, they’re taking back the water, one step at a time. They walk the perimeters of lakes, the lengths of rivers. They walk across nations.

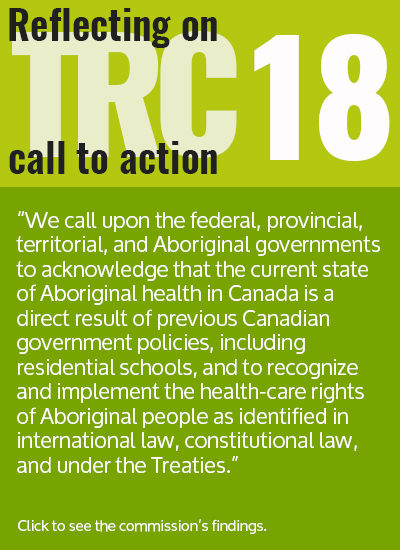

When a grand chief of the Three Fires Midewiwin Society predicted that by 2030 “an ounce of drinking water will cost the same as an ounce of gold,” Josephine Mandamin of the Wikwemikong First Nation laced up her sneakers. She co-founded Mother Earth Water Walk with a mission to “raise awareness that our clean and clear water is being polluted.”

Mandamin walked around Lake Superior. Then Lake Michigan. Since 2003, the 74-year old has walked more than 20,000 kilometres and inspired hundreds of “water walkers” to follow in her footsteps.

“We will go any lengths for the water,” Mandamin stated in a news release accepting the 2016 Lieutenant Governor’s Ontario Heritage Award for Excellence in Conservation.”We’ll probably even give our lives for the water if we have to.”

Toxic waters

Grassy Narrows. Shoal Lake No. 40. Neskantaga. These are places where drinking water comes in bottles, where babies can only be sponge bathed, where, as Isaac Murdoch drives toward home on the Serpent River First Nation, an hour and a half north of Sudbury, five-gallon water jugs weigh down the backseat of his car.

“It’s pretty tough,” Murdoch says of living without safe drinking water for most of his life. “I even notice when I’m at a friend’s house that I find myself not using their water because my mind is trained not to drink out of the tap.”

Last September, Murdoch’s community was celebrating the opening of Serpent River’s water treatment plant with a ribbon cutting ceremony. Two weeks later, the plant stopped working.

Nearly twice Health Canada’s standard limit of Trihalomethanes (THMs)—a disinfection by-product containing compounds such as chloroform—was contaminating the water. According to the World Health Organization, such levels may cause several types of cancer. Health Canada told Serpent River Chief Elaine Johnston, a registered nurse and former health director of the Assembly of First Nations, the risk was negligible. Johnston didn’t agree.

“In a community already at risk, I do not want to increase that risk,” she says.

In 1993, two million litres of uranium tailings from Rio Algom’s Stanleigh mine spilled into McCabe Lake, destroying the Serpent River watershed. Canadian Nurses for Health and the Environment report 165 million tonnes of radioactive tailings remain in the area, and that the people of Serpent River “still experience severe environmental, health, social, cultural, and economic impacts.”

It’s April now and Chief Johnston sits in the band office wondering what went wrong. Her community began the water treatment facility’s planning process 21 years ago. Johnston recounts discussions, proposals, negotiations, redrafts of proposals.

“Too many, as a matter of fact,” she says. “The government needs to change the way it does business with First Nations.”

Nazko. Pinaymootang. Kashechewan. States of emergency declared. Children with mysterious skin rashes evacuated. The story repeats itself. What starts as a drop fills a bucket.

Some First Nations people, such as Murdoch, are angry. “I feel like I want to revolt. I feel like a huge injustice has taken place.”

Others are tired of being dependent. “I’ve had some of the Elders tell me they’re going to drink the water anyways,” Chief Johnston says. “They say, if I get cancer, I’ll take the chance.”

A promise of change

In 2010, the United Nations passed a resolution declaring no one should have to take such a chance. Safe drinking water is now a human right. In 2012, Canada recognized this right but has yet to implement federal legislation. According to the David Suzuki Foundation, Canada is the only the only G8 country “without legally enforceable drinking-water standards.”

Emma Lui, water campaigner for the Council of Canadians, says, “Drinking Water Advisories in First Nation communities remain one of the greatest violations of the human right to water.”

While the Liberal government has promised to spend $2.24 billion to end all DWAs within the next five years, Lui thinks ending DWAs only scratches the surface.

“There needs to be a bigger discussion,” she says, “about Indigenous treaty rights, title to land, water rights. It’s important to recognize First Nations as their own government, to establish a nation-to-nation dialogue.”

Erin O’Toole, former cabinet minister and current Conservative MP for Durham Region, says it’s not so simple.

“In Ottawa now they talk a lot about nation-to-nation dialogues. But there’s over 600 First Nations, so nation-to-nation is not one-to-one, it’s Canada to hundreds.”

The gap

There are other reasons why it’s complicated. O’Toole recalls his former neighbours, the Mississaugas of Scugog Island First Nation (MSIFN).

“On my old street you were in the municipality of Scugog, subject to provincial laws and regulations,” he says.

Walk across the street and into the reserve? Federal.

The MSIFN reserve, 65 kilometres northeast of Toronto, has been affected by DWAs since 2008.

A small step, a big gap.

This gap can be costly. While the federal government provides funding for approved projects and 80% of operating costs, First Nations are responsible for designing, building, operating, maintaining and monitoring water treatment facilities. For smaller First Nations, this gap can mean millions they simply don’t have.

“The gap is unjust,” says Deborah McGregor, Associate Professor at York University and a Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Environmental Justice. “There are structural, political and legal processes in place that create the situation that’s in First Nations communities.”

One such structure, the reserve system, grants the federal government jurisdiction of “Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians” by order of the Constitution Act of 1867. Critics of the system call it a “disgrace,” a “fortress,” a “sickness.” And nothing, according to many First Nations, symbolizes this sickness more than the state of the water.

As he drives past the river that was once “the lifeline” of his village, Isaac Murdoch thinks the equation for Canada’s reconciliation with First Nations is simple.

“Clean water means good reconciliation,” he says. “Water not so good means reconciliation not so good.”

Water is a relative

Lake Babine. Kitigan Zibi. Eabametoong. Water not so good. So many lifelines destroyed. Water treatment facilities have become what many call “band-aid solutions” to what flows beyond reserve boundaries.

“What’s off-reserve versus on-reserve water?” McGregor asks. This is not just a reserve issue, she says. This is not just about a clean glass of water. It’s about fundamentally different beliefs.

“It is risky to treat First Nations as a homogenous group,” states the 2006 Expert Panel on Safe Drinking Water for First Nations. “If there was one area, however, in which attitudes were widely shared, it was traditional beliefs and attitudes toward water.”

Non Indigenous people in Canada tend to view water as a resource, a commodity. “Or, if you’re taking your direction from the UN,” McGregor says, “as a human right. But Indigenous people see the issue more broadly. Water isn’t a commodity. It’s a relative.”

Walking for water is one way First Nations are attempting to bridge the gap between these different perceptions.

Water is a relative. Water is alive. Water is protected by Indigenous law. People have a responsibility to care for the water. These are some of the teachings Professor Emeritus at Trent University and Anishinaabe Elder Shirley Williams says have been forgotten because of years of oppression and assimilation.

Williams, a residential school survivor, says, “My parents taught me to look at the water as a sacred thing because it has a spirit. So if you have a spirit you don’t destroy that spirit. You attend to it.”

Inspired by Josephine Mandamin, Williams helped organize Nibi Emosaawdamajig, Ojibwe for “those who walk for the water,” to attend to the spirits of the Kawartha Lakes region. Since 2010, the group has walked more than 1,000 kilometres.

Georgie Horton-Baptiste by the Odoonabii-ziibi (Photo: Georgie Horton Baptiste)

Three Reasons to Walk for the Water listen

“We are in a crisis right now because we haven’t learned to take care of the water,” Williams says.

According to the 2015 UN World Water Development Report, the grand chief of the Three Fires Midewiwin Society may have been right. Unless we do what water walkers such as Williams advise and stop viewing water as “just a thing that will be here forever,” the UN warns of a worldwide water crisis by 2030.

Water Walk Organizer Georgie Horton-Baptiste sits on the couch in her Peterborough living room, planning for this year’s walk along waterways with names like Odoonabii-ziibi—“river that beats like a heart.”

“Water is neutral,” Baptiste says looking out at the ice-covered branches. “I am water and you are water, that’s our connection.”

A clock ticks in the background. Photos of water cover the walls. Drops. Ripples. Waves.

“We may be of different nations and different races and come from different places,” she says, “but the water connects us all.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated the year Josephine Mandamin won the Lieutenant Governor’s Ontario Heritage Award for Excellence in Conservation. The reporter regrets the error.