Photo: Wiki Mechanics/Flickr

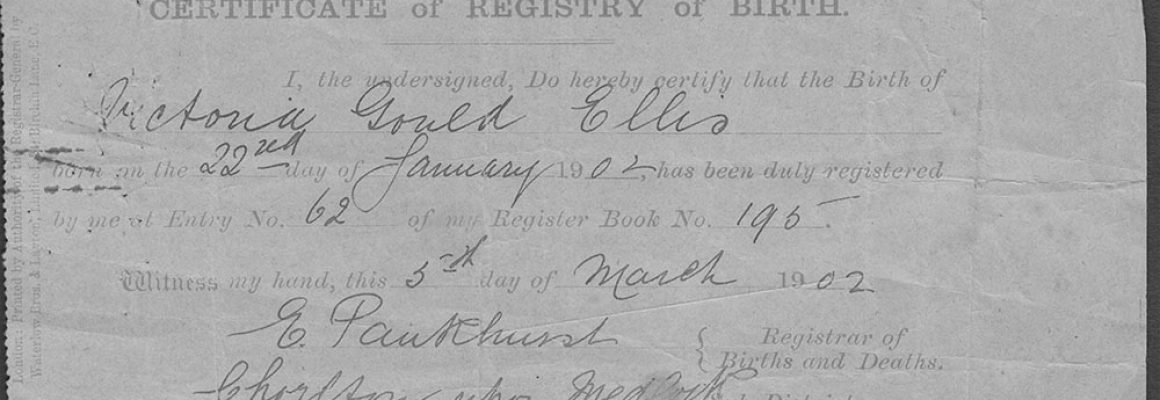

From the moment Lynn Gehl was born she was disadvantaged within her cultural community and all because of a piece of paper.

Though she self-identifies as Algonquin Anishinaabe-kwe, though she participates in this cultural community and though she advocates for Indigenous rights, it is not enough for the Canadian government who have denied her Indian status.

Gehl’s paternal grandmother was a status Indian, but her grandfather’s signature is missing from her father’s birth certificate. This is what is called “unknown or unstated paternity” and due to stipulations in the Indian Act if a child’s father is not known then they cannot obtain status.

“The fathers are just assumed to be white men,” explained Gehl, who holds a doctorate in Indigenous studies. “There are good reasons to leave out the paternity.”

Gehl sent a status application to the government, but in 1995 it denied her request. She then spent decades fighting this decision, which culminated in a court battle in October 2014.

“The Indian Act is racist and sexist,” said Gehl. “I want to protect mothers and grandmothers from it.”

On June 2nd 2015, the Ontario Superior Court ruled that the Indian Act does not disadvantage those with unstated or unknown paternity. The reasoning behind this decision was that if the law changed then people could take advantage of it and claim that their unknown parent had status in a ploy to get benefits.

“The trial was unfortunate, unsatisfying and traumatizing,” said Gehl.

The meaning of status

Gehl’s story represents the complicated nature of status.

A status Indian is an individual recognized by the federal government as being registered under the Indian Act. This act, which was passed in 1876, is a statute that dictates the federal government’s relations with Indigenous peoples and it outlines who receives status from the Canadian government. If someone is a status Indian, then they can receive a variety of benefits that are not available to the rest of the population.

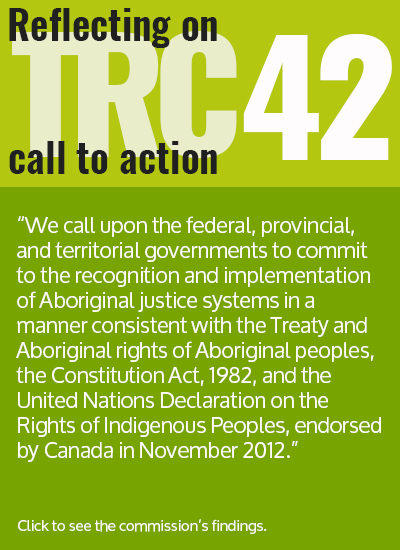

But since its inception the Indian Act has been a point of controversy, because many believe it attempts to weed people out of Indigenous communities. In a paper written by Joan Holmes & Associates Inc. titled “The Original Intentions of the Indian Act,” it states: “Both the Indian Act and the Indian Department have evaded every attempt at substantial reform. As such the oppressive, restrictive and discriminatory principles of this 19th century legislation have been carried into the modern era.”

“Over time people have internalized status as the recognition of Indigenous identity,” said Claire Truesdale a lawyer at JFK Law Corporation, who deals primarily with Indigenous issues in her work. “They reject the idea that Canada should decide who is Indigenous.”

One of the biggest issues with the Indian Act is the fact that it disadvantages women. Until 1985 if a status woman married a non-status man she lost her status, but this same rule was not applied to a man if he married a non-status woman. After the creation of Bill C-31 this rule no longer exists, but many Indigenous people still feel the impact of this former regulation.

“The Indian Act should eliminate these residual effects against women,” said Truesdale. “It needs to give the power to those who belong to the community.”

The story of Dawn Lavell-Harvard

Dawn Lavell-Harvard knows all too well about the discriminatory nature of the Indian Act. She is the president of the Native Women’s Association of Canada and she is also the daughter of Jeannette Corbiere Lavell, who was the first person to go to court over gender discrimination in the Indian Act after losing her status to marriage.

Lavell-Harvard said that she did not have status before the implementation of Bill C-31, but because her mother was a teacher on a reserve she still received many of the same benefits. She then added that she was “a part of a larger political conversation” and that “she grew up with no choice but to be political.”

“The Indian Act is unquestionably sexist,” said Lavell-Harvard. “It’s made very clear that men are the only people deserving of full personhood.”

What Lavell-Harvard sees as problematic with the Indian Act is what countless others see as well: The Indian Act gives the Canadian government the right to decide who is Indigenous and who holds power in the community.

“It creates community dysfunction. It creates violence. It creates disruption,” said Lavell-Harvard.

Problems with the Indian Act

The Indian Act does not take into account if a person identifies as Indigenous. It does not know if a person practices Indigenous traditions. It does not care if a person has lived their entire life on a reserve. All it is concerned with is whether or not one of your parents or grandparents have status or who you are married to.

This act of measuring how Indigenous a person is determined by a concept called blood quantum. Blood quantum is used for legal purposes and posits that a person’s blood comes 50 per cent from their mother and 50 per cent from their father. So if a person has one parent with status and one parent without it, then their blood quantum is 50 per cent. But if that same person goes on to marry someone who is not Indigenous, then their children’s blood quantum will be 25 per cent. A child with 25 per cent blood quantum cannot receive status.

“We are more than just a status card or a number,” said Lavell-Harvard. “My family didn’t become more Indigenous when we got status.”

What things like blood quantum and the Indian Act do is eliminate Indigenous culture, because they place arbitrary restrictions on what makes somebody Indigenous. In an article in The Ethnic Aisle titled “Blood fiction: belonging, services and status Indians,” Pamela D. Palmater, who is a Mi’kmaq lawyer and professor, wrote: “There is a long-term effect of this type of legislation: that every single First Nation in Canada effectively has an extinction date, a day when that Nation’s last registered Indian is born.”

What status looks like today

Though there have been attempts to abolish or completely overhaul the Indian Act, such as The White Paper, The Manitoba Framework Agreement and The First Nations Governance Act, none of them have found great success. Gehl, Truesdale and Lavell-Harvard all said that the Indian Act does not need to be abolished completely, but rather it needs to be replaced with something that protects, not eliminates Indigenous culture. Truesdale suggested that a good start would be to get rid of the “old-fashioned and outdated” concept of blood quantum and to better staff the the Indian Registrar.

On April 14, 2016, the Supreme Court of Canada unanimously ruled that the federal government has a constitutional responsibility for Métis and non-status Indians. Though this is a positive development, it does not mean that there will not be problems in the future. Lavell-Harvard described this ruling as a “first step in helping to address the wrongs and remove the divisions from the harm that was done.”