Chris Pike offers to self-disclose. He went in for a specialist appointment last year, and when asked about his lifestyle, said he identified as a therapist and a sober person. Alcohol isn’t traditional so he doesn’t drink, do drugs or smoke commercial tobacco. When he told his two doctors of his participation in sweat lodges, they referred to this ceremonial participation as an “odd and secret ceremony.”

Chris Pike offers to self-disclose. He went in for a specialist appointment last year, and when asked about his lifestyle, said he identified as a therapist and a sober person. Alcohol isn’t traditional so he doesn’t drink, do drugs or smoke commercial tobacco. When he told his two doctors of his participation in sweat lodges, they referred to this ceremonial participation as an “odd and secret ceremony.”

That in 2015, doctors at a major downtown hospital would say that is “quite disturbing,” he said. Pike, a clinician and therapist, who identifies as two-spirit, is a proponent of culturally safe healthcare, a major focus of his employer, Anishnawbe Health Toronto (AHT). Large pieces of that approach require understanding the myriad ways individuals experience their identities, how that relates to culture and respecting how those facets have been affected by legacies of colonization and residential schools.

“Homophobia, transphobia and two-spirited phobia is not traditional,” says Pike. While no two communities are the same, many have undergone drastic adaptations in the way they interpret, react to and welcome gender diversity. These variations have had lasting and intergenerational effects on how Indigenous youth’s identity and health will fare.

“Homophobia, transphobia and two-spirited phobia is not traditional."

Two-spirit, third and fourth gender are just some of the gender identities given names by Indigenous communities, with countless more being represented in Indigenous languages. Two-spirit, a term founded at a Winnipeg conference in 1990, is a derivation of the Ojibwe and Anishnabe term niizh manidoowag, or “two spirits.” It means something different to many, but the phrase, designed to help recover pre-colonial ways of being, often signifies a person’s dual embodiment of masculine and feminine spirits. Traditionally, two-spirited and gender nonconforming people were revered in their communities, given high ceremonial roles and access to male and female duties.

While the legacies of colonialism and residential schools have had far-reaching intergenerational impacts on Indigenous communities across Canada, two-spirited people have experienced distinct setbacks. Once revered, Christianization and the inflection of patriarchal and heteronormative standards had two-spirited people stigmatized for the first time.

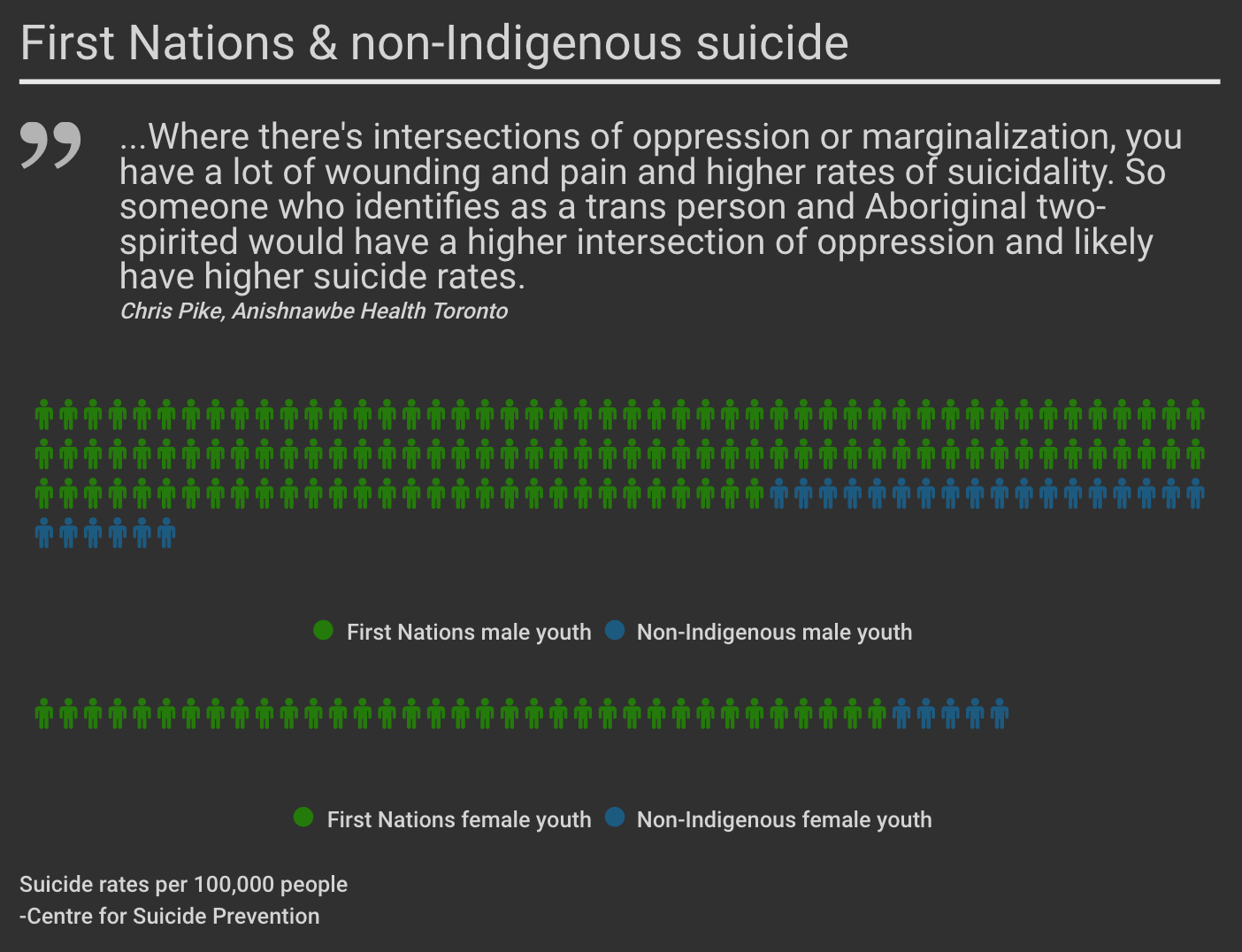

This stigma has material consequences in health. Both Indigenous and queer youth are disproportionately represented in local and national populations experiencing homelessness, at risk to attempt suicide or to experience violence. “Where there’s intersections of oppression or marginalization, you have a lot of wounding and pain,” says Pike.

“It’s not just a health issue: it’s a social issue,” says Nicole Tanguay, who has lectured on social determinants of health, worked as an HIV/AIDS educator at AHT and works with the Native Youth Sexual Health Network (NYSHN). “It’s about how we feel about ourselves and how other people treat us.”

“It’s not just a health issue: it’s a social issue..."It’s about how we feel about ourselves and how other people treat us.”

But because the notion of two-spirit identity lives at the intersection of identity and culture, the approach to healthcare provision follows suit, lending itself naturally to holistic approaches.

“Culture is healing,” says Pike.

AHT, and providers that practice cultural safety like it, don’t compartmentalize aspects of wellness– self-esteem, culture, land and justice all have roles to play in healthy bodies.

And, all these elements affect individuals uniquely: “We try to contextualize people’s problems here, so a lot of what many practitioners in dominant culture would see as a diagnosis we see as a natural consequence of colonization,” says Pike.

AHT is unique in offering wraparound healthcare in both Western and traditional models. Pike estimates that 60 per cent of their staff are Indigenous, offering their clients a “mirror” and the option of biomedical or traditional treatment that they’re most comfortable with. It’s important to “make space where people see that they’re reflected and they’re welcomed,” says Pike.

Tanguay, who works across social work and the arts, agrees on the importance of having healthcare staff that represent their patients. Tanguay discusses the deployment of non-Indigenous workers to the mental health crisis unfolding in Attawapiskat. According to them, that approach perpetuates the problem.

“You think you’re saving us? You’re making things worse,” they said.

Tanguay has spent the last 30 years working as a social worker, and is now focusing on the integrative healing power of art and social service. Tanguay currently conducts two-spirited skills-sharing and writing workshops with youth at NYSHN that explore the meaning of two-spiritedness.

‘There’s more work to be done’

Kira Vallen says she learned more about herself off the reservation than on, and dreams of going to visit the Smithsonian to see the history of trans people. She says you can call her the “Trans Grandmother.” Sitting on a bench outside Allen Gardens on the first palpable day of spring, Vallen calls over someone she recognizes across the way, who runs over to hug her. This person looks barely 20 and thin, wearing a leather jacket and missing most of their front teeth. They tell Vallen they’ve just skipped out on detox at the hospital, not being able to hack the methadone, and ran off from their boyfriend after getting stabbed. But they said they’re hanging in there.

“She is a suicide candidate on reserve,” says Vallen.

But Indigenous, particularly two-spirit, third gender and queer youth, flock to cities to find community in each other, she says, and gain access to health services geared towards them. Vallen says that on reserves, “You don’t have Women’s Health across the street,” as she points behind her, “or the Anishnawbe Health two-spirit sweat.”

Vallen, who identifies as third-gender from the Saugeen First Nation, says that people “are more accepting of transgender Natives” in cities than on reservations: “Where would you want to be? Where I’m accepted or not accepted?” she posited.

But those social determinants of health exist everywhere.

Art Zoccole, the executive director of 2-Spirited People of the 1st Nations, says that all First Nations and communities approach gender diversity differently, but some areas are reliably less hospitable than others.

Zoccole, who is from Northwestern Ontario and has done a lot of foundational research on HIV/AIDS and Indigenous communities, says he thinks that two-spirited people are accepted in many rural areas like Fort Francis, Kenora, Dryden, and Thunder Bay area. “But if you go further north,” says Zoccole, “to the fly-in communities, there seems to be more stigma and discrimination against two-spirit communities.”

In places that feel forgotten, like Attawapiskat, people are out of care’s reach, says Tanguay. And, despite increased attention to this one community in the wake of its emergency declaration, Tanguay observes that, despite general knowledge about mental health risk factors, no one has addressed how many of the youth suicides there are two-spirited.

Despite general knowledge about mental health risk factors, no one has addressed how many of the youth suicides [in Attawapiskat] are two-spirited.

Last year, Toronto opened its first LGBTQ shelter. Street Needs Assessment data reflect the disproportionate rates of queer youth homelessness, and mental and sexual health outcomes. But in a city with a large and growing Indigenous population, not as much is known about Indigenous health outcomes for two-spirited youth.

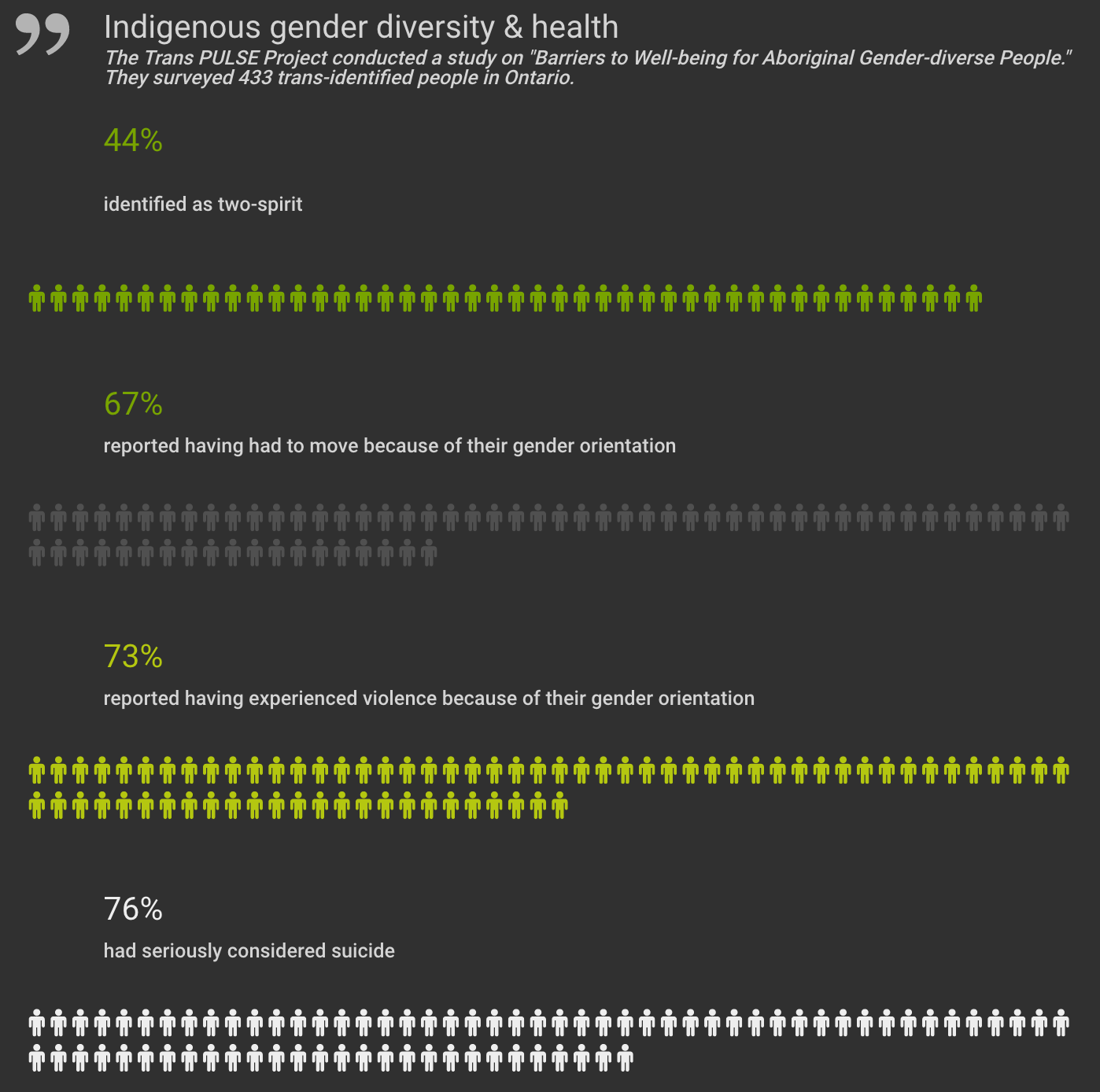

In 2008, researchers Shari Brotman, Bill Ryan, Yves Jalbert and Bill Rowe wrote about a dearth of information on two-spirit health outcomes in queer academia. According to them, “few practitioners, policy makers or researchers in the field of glbt health are even aware of the term Two-Spirit.” And, according to the National Aboriginal Health Organization, studies that included transgender and two-spirited people in Ontario showed that 28 per cent had attempted suicide because of ways that have been treated due to their identity. Different communities have different health outcomes, but national averages reflect that suicides in First Nations are twice the rest of the Canadian population.

In 2008, researchers Shari Brotman, Bill Ryan, Yves Jalbert and Bill Rowe wrote about a dearth of information on two-spirit health outcomes in queer academia. According to them, “few practitioners, policy makers or researchers in the field of glbt health are even aware of the term Two-Spirit.” And, according to the National Aboriginal Health Organization, studies that included transgender and two-spirited people in Ontario showed that 28 per cent had attempted suicide because of ways that have been treated due to their identity. Different communities have different health outcomes, but national averages reflect that suicides in First Nations are twice the rest of the Canadian population.

Some are concerned about the invisibility conferred by the sheer lack of information on two-spirit and gender nonconforming Indigenous youth: “It’s just very telling,” says Pike. “I think it goes to the hidden nature of our community, that there’s more work to be done.”

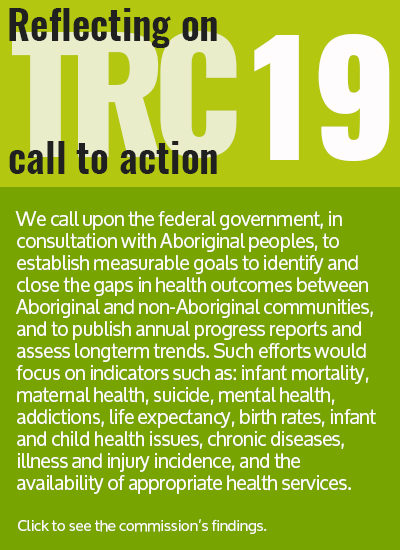

But, he feels that through community-based and culturally safe programs, and increased openness in the wake of the TRC’s report, increased awareness can create space for two-spirited communities: “As we each do our healing work and our wellness work, and the TRC’s part of that for some of us, we will have our voice,” says Pike. “As more of us get healthy and well, and we support each other to get more healthy and well, we will just have our space in that alphabet soup of queer identity. Because we have a very unique space.”

Related link: To read more about the role of colonization in the history of two-spirit people, please click here to read Mike Ott’s piece, “Taking a Walk in Two Worlds.”