It’s February in Rankin Inlet, a predominantly Inuit hamlet on the northwest coast of Hudson Bay. It’s very cold outside—about minus 30 degrees Celsius—making the bag of grapes Bernadette Dean is holding more than a little out of place. “I find it so bizarre,” she says, “to see on a cold winter day, a ‘product of Chile,’ or ‘product of California.’ It’s cold and I see this—I don’t even buy it. Who picked it? How did it get here? It’s not our traditional food.”

“The ones that complain about the high cost of living,” she adds, “are probably senior bureaucrats from Toronto that are used to foods like that.”

Senior bureaucrats’ recent efforts amounted to Nutrition North a federally administered $60-million-per-year subsidy for shipments of healthy groceries to northern communities. It landed with a thud. An auditor-general’s report found little evidence that the subsidy was being passed onto consumers. Critics call it an abject failure.

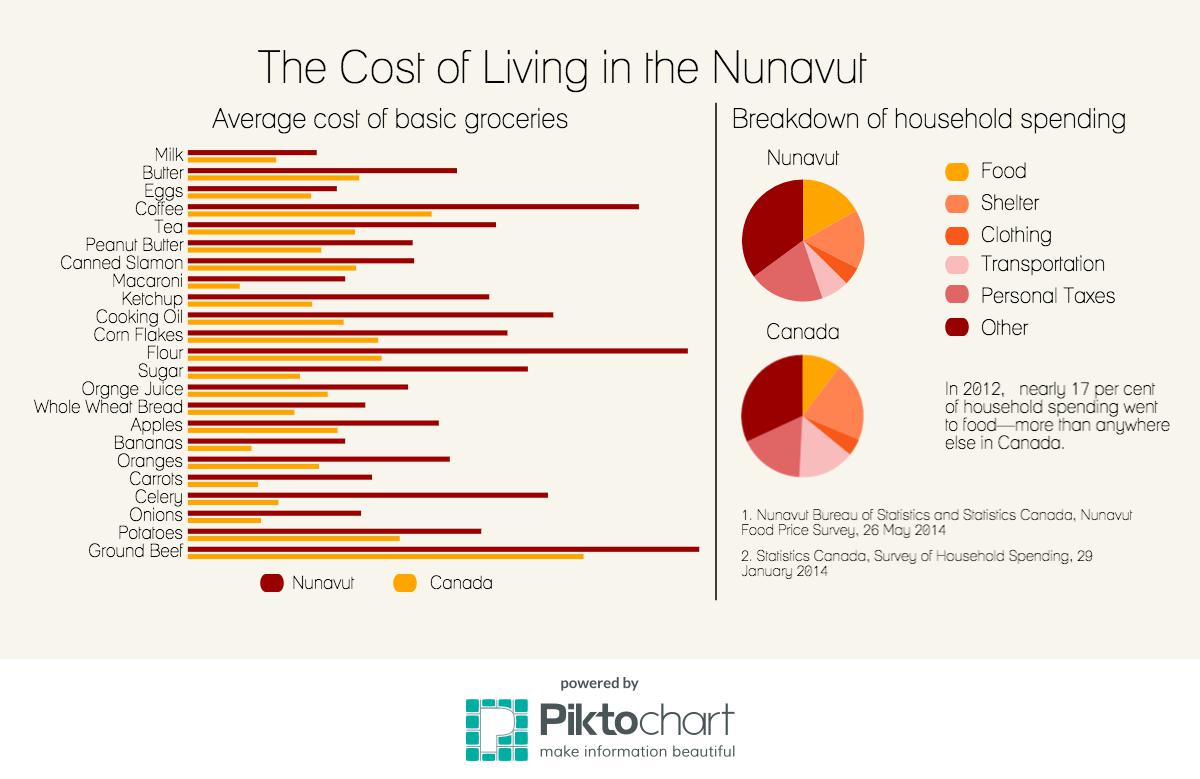

Dean is only half right—living up north is expensive. That bag of grapes Dean picked up from the Northern Store shelf runs $16.59 in Rankin Inlet; at Loblaws in Toronto, a bag of grapes is $11. Item for item, price increases vary wildly, from as little as 20 per cent more for eggs, to 287 per cent more for celery—the fresher and more perishable, the pricier. In Nunavut, Health Canada estimates that feeding a family of four a healthy diet costs $430 weekly. Yearly, that’s more than $22,000. The median annual income for Nunavut’s Inuit is $19,900. In Toronto, week’s worth of healthy groceries costs about $200. The fallback from clean protein and fresh produce is nutritionally bereft, carb and sugar-dense processed food. It’s just cheaper, and in recent years, the rates of obesity, diabetes and anemia amongst Inuit youth have skyrocketed past the national average.

That crisis is a symptom of food insecurity, which, unsurprisingly, is endemic. The state is an aggregation of conditions, including concern about running out of food before being able to buy more, the inability to afford healthy food, missing meals, and at its worst, not eating for a whole day. A 2014 study published by the University of Toronto pegged food insecurity at 46.8 per cent in Nunavut. In 2008, a Health Canada-sponsored survey found that Aboriginal communities in Nunavut suffer from the highest rate of food insecurity of any Indigenous population of any developed country in the world.

Harvesting the Backyard Bounty

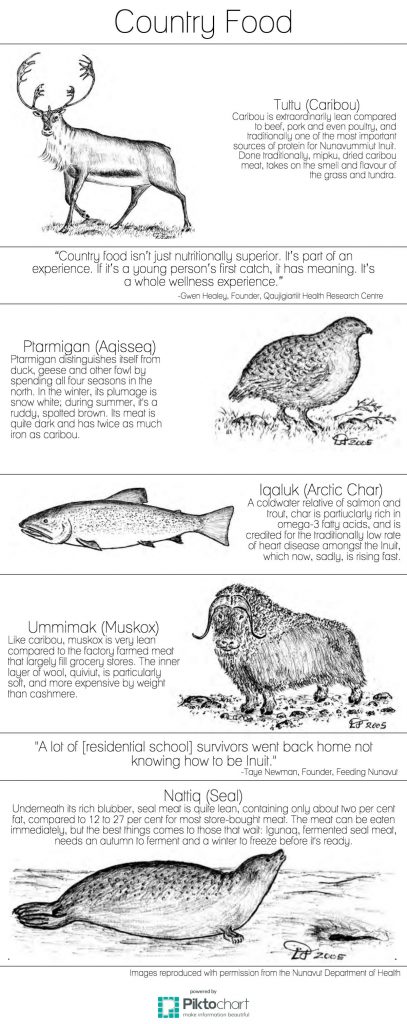

Dean didn’t buy the grapes. She didn’t need to buy much else, either. Her family, she tells me, is very traditional, and she eats well. Her husband, brothers and son-in-law all hunt, at least occasionally, and, she stresses, they’re skilled. “I have access to country food all the time,” she tells me. That means caribou, char and seal, amongst other game. It’s the traditional Inuit diet. Dean acknowledges her fortune; she knows not all families are so lucky.

In some communities, Dean says, residential schools eroded the familial bonds required to pass on traditional knowledge, and it’s not skill set that lends itself to a crash course. “We have generations affected by residential schools,” Dean explains. Her brothers grew up hunting, waking up before dawn to make good on short days and learning how to read the weather, migration patterns and the ice floes, all at-home, life-long lessons that residential schools interrupted for thousands. A Council of Canadian Academies report on Nunavut’s food insecurity echoes Dean’s observations. “Systematic disempowerment,” its authors say, has “clear implications for intergenerational knowledge transmission and local environmental knowledge.”

It’s not cheap, either. The capital investment to harvest country food year-round is immense. A rifle is about $1,200. The ubiquitous ski-doos, “machines,” and all-terrain four-wheelers cost approximately $10,000 apiece. The gear for fishing, including a boat, outboard and trailer, costs more than $30,000. Overall, with incidentals, it’s about a $56,000 investment for harvesting start-ups. But the payoff can be huge. For a few hundred dollars-worth of gas, a successful trip can yield 1200 pounds of caribou, or 800 pounds of muskox. A trip out in the boat can produce two to three hundred pounds of Arctic char. It’s a question of investment: Could the $60-million being poured into programs like Nutrition North be better served improving hunting capacity?

“I don’t think so,” says Todd Johnson, who manages Kivalliq Arctic Foods in Rankin Inlet. “Without artsy-farsty outside interference, I know it can help. I’ve seen it. I’ve lived it.” Johnson’s operation is one of three major processors and distributors of country food in Nunavut. Its trademark is the Country Pak, approximately ten kilos (depending on the season) of wild caribou, muskox and char that he sells for an even $200. Per kilo, that’s $9 cheaper than beef roast, $11 cheaper in sirloin and less than half as much for t-bone. Per kilo, it’s cheaper to reap the bounty from the backyard than to fly it in. He goes through less than he used to, though. Johnson, who’s lived in the north for 16 years, says there are fewer and fewer hunters.

Bureaucrats are catching up to Johnson’s gut feeling. Last year, the Government of Nunavut listened to the chorus of studies—the CCA study amongst them—calling for an investment in harvesting and set up the Country Food Distribution Program, a subsidy issued to communities to improve and repair infrastructure (in particular the ubiquitous and often dilapidated community freezers required store meat) and toward community-identified initiatives. The latter often means simply reimbursing hunters for their expense. Owing to tradition, they would often share their haul with everyone, but the money economy made it unsustainable. The CFDP fills that gap. Between investing in freezers and community initiatives, municipalities are eligible for up to $40,000. In total, the CFDP spent $300,000 in its first year.

In Rankin Inlet, that meant money for Country Paks, which meant money for Kivalliq Country Foods, which meant money for hunters to hunt. It meant priority access for low-income families, and it meant money staying in the community. It meant a local economy thriving off of tradition, not languishing with grapes from California or Chile. At this point, the results are anecdotal, but Johnson, who’s keenly aware of the program, says the community has been generally supportive.

Dean isn’t so sure. “The thought of selling meat instead of giving or sharing it—it’s the biggest sin you can commit.” Her anguish touches on the intertwined Inuit values of food, sharing and community, a triad existing outside of a money economy. Its upkeep is an extraordinarily sensitive subject, and some, like Dean, feel that buying and selling country food threatens it. Johnson is of two minds. He sees hunger and insecurity—he’s attended conferences on the subject in Iqaluit—and just wants to provide country food as cheaply as possible. He thinks the CFDP can do that. Unhappily, though, he elegizes the past. “Sharing was the way, not a way. It’s gone, though, just because of our society.”

Gwen Healey was born and raised in Iqaluit, left to pursue her PhD in public health at the University of Toronto, then returned home and founded the Qaujigiartiit Health Research Centre in 2006. For all the complexities of public health, and the added complexity of public health in the north, her approach is simple: focus on Nunavut’s strengths, and country food is undoubtedly one of its greatest. She teaches Inuit youth, and grew up eating it—ptarmigan is a favourite. She’s keenly aware of the traditional values Dean is reluctant to jeopardize, but knows that country food is healthier, available and culturally appropriate, transacted or not. But it’s pitted identity against health, and southern food is a constant presence. Besides, grapes are part of northern life now.

They’re not of the north, though. “It’s about familiarity and comfort,” says Healey. “Country food isn’t just nutritionally superior. It’s part of an experience. If it’s a young person’s first catch, it has meaning. It’s a whole wellness experience.”

Going Forward

Dean gently reprimanded me when I asked if she was seeing a turn back to hunting. “There’s no back. We’ve always hunted. We never stopped hunting.” And she’s right, the majority of households in Nunavut have an active hunter. It’s not ordinary anymore, though. For many, it’s a weekend sojourn, a part-time trip, and youth have fewer opportunities to learn from their elders. Residential schools disrupted hunting’s regular practice, and the imposition of a cash economy polluted the tradition. Climate change is eroding sea ice, provoking unpredictable weather patterns and making travel more difficult. Every trip is even more precarious than the one before. Overhunting caribou on Baffin Island prompted a moratorium in 2014. Even the most optimistic are anxious about country food’s future.

Nunavut is hungry, Inuit households disproportionately so. Food insecurity is a mute, lingering violence. It’s a hangover from decades of assimilationist policy. But tradition is resilient. Inuit never stopped hunting. It’s not a dead skill, and in the short term, it can coexist with a cash economy. It can accommodate climate change. It can be practiced sustainably. It can be expanded, rejuvenated, and it can feed a lot people, every bite a reassertion. Bernadette Dean says that, in her dialect, hunting translates to angunasungniq, which also means the ongoing journey of becoming a man. Hunting is necessity, rite and, owing to humility, never mastered.

At five years old, Gwen Healey’s daughter went out with her father, came home, and held up her first ptarmigan. “I brought this home for you.” It was the best day of her life. Inuit never stopped hunting.