|

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Article 29: “Indigenous peoples have the right to the conservation and protection of the environment and the productive capacity of their lands or territories and resources. States shall establish and implement assistance programs for indigenous peoples for such conservation and protection, without discrimination.” On May 10, 2016, Canada officially became a full supporter of the declaration, with intention to implement it. |

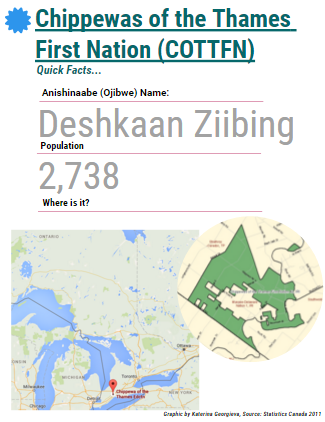

The Inuit people of Clyde River and the Aboriginal people of Chippewas of the Thames First Nation (COTTFN) are demanding that the Crown honour its duty to consult them on projects that affect their lands and livelihoods, in accordance with constitutional law.

The Inuit people of Clyde River and the Aboriginal people of Chippewas of the Thames First Nation (COTTFN) are demanding that the Crown honour its duty to consult them on projects that affect their lands and livelihoods, in accordance with constitutional law.

Canada has a legal duty to consult and accommodate Aboriginal, Inuit and treaty rights on all developments that have the potential to undermine their rights and livelihoods.

“The process is faulty,” said Chief Leslee White-Eye of COTTFN. “There’s no responsibility on the crown to uphold its duty to consult.”

In November 2016, both Clyde River and COTTFN will be heard together, by the Supreme Court of Canada.

Nader Hasan, the lawyer representing Clyde River’s case, said that, “Win or lose…it’s going to set a leading precedent going forward on the scope of the duty to consult.”

The two communities have joined forces to fight two projects that were green-lighted by the National Energy Board (NEB). They both want the same things, explained Chief Leslee White-Eye, of COTTFN, which is, “a process that’s respectful of how we expect to be consulted, and for us to have a say in the development of how that process is being undertaken.”

A forty-year-old Enbridge pipeline spans from North Westover to Montreal. It runs through the Thames River, passing through the north end of COTTFN’s traditional territory, in southwestern Ontario. In July 2012, the NEB approved Enbridge’s reversal of the oil’s flow direction, while also allowing for an increase in the volume of crude oil passing through the Line 9 pipeline, inspiring concerns from leaders about leaks and spills.

The Inuit of Clyde River, Nunavut, rely on hunting narwhal and other marine animals for their diet. In June 2014, the NEB approved the licensing for TGS-NOPEC Geophysical Company (TGS), Petroleum Geo-Services Inc. (PGS), and Multi Klient Invest (MKI) to conduct seismic testing on the shores of Clyde River, in Baffin Bay and Davis Strait, potentially disrupting marine life in the process.

Enbridge and the Geophysical companies conducted their own consultation efforts, but according to Hasan, it is “the obligation of the government, not private companies, to consult with Aboriginal peoples.”

LISTEN: “Taking Aboriginal rights seriously, means that they prevail, even when the interests of the oil and gas sector or the provincial government are in play. …That’s what these cases are about.”

– Nader Hasan, Lawyer for Clyde River

Clyde River

In April 2013, the NEB held a public review meeting of the seismic project application in Clyde River, inviting people from the community to come forward and express their concerns at Tuqqayaq Community Hall.

Jerry Natanine stood up to say, “I wish that their ship will never go to our waters. I hope that they’ll never do what they want to do, kill off our animals.”

He went on to become mayor of Clyde River from December 2013 to December 2015, and is the man spearheading the fight to stop seismic testing.

Nonetheless, the NEB approved the 5-year seismic project, off the shores of Clyde River, intended to map out where to find undiscovered oil beneath the arctic floor. The project has been stalled by the ongoing court battle.

LISTEN: “…The first step to drilling for oil, is seismic blasting…”

– Farrah Khan, Arctic Campaigner, Greenpeace Canada

“Clyde River Community 1997-08-07” by Ansgar Walk is licensed under CC-BY 2.5

Upon reaching the NEB for comment, Tara O’Donovan, a representative, said, “We’re always seeking to engage Indigenous groups in our processes, as we did in both of these processes.”

Hasan said, “Our view is that once seismic testing begins, you can’t put the genie back in the bottle.

“There will be irreparable harm to marine life, the ecosystem, and of course, to Inuit food security,” he stressed.

Food security is already a serious issue in the north. Leyland Cecco, a journalist who spent some time working in Clyde River in 2015, said that, “Food security isn’t manifested in a lack of food, it’s in a lack of quality food, which is very systemic up there.”

LISTEN: “There are certainly households in Clyde that are poorly nourished, because they are mainly dependent on market foods…”

– Dr. George Wenzel, Professor of Geography, McGill University, and former resident of Clyde River

Chippewas of the Thames First Nation

George Henry, band council member and traditional knowledge keeper, says the people of COTTFN weren’t consulted when Line 9 was originally built in 1975.

Now, Enbridge has already moved forward with its most recent modification plans of the pipeline, as approved by the NEB.

“That pipeline is flowing,” said Chief White-Eye. “It’s flowing as Enbridge has requested it to.”

Along with the change in the oil’s direction, the modification of the pipeline included an increase in the amount of oil flowing through the pipeline, from 240,000 barrels to 300,000 barrels per day.

LISTEN: “Our whole reason for this is the protection of water, which is our responsibility as First Nations, Indigenous People…”

– George Henry, COTTFN Band Council Member, Traditional Knowledge Keeper

Henry is a political adviser, as well as a traditional knowledge keeper about the use of land, water and air. This knowledge has been passed down orally, he explained, going back, maybe 10,000 years.

“Thames River Springbank Park” by Abdallahh is licensed under CC BY 2.0

He stated that, “we have the responsibility as First Nations people to look after this land, Canada, the western hemisphere.”

LISTEN: “We follow a natural law, which Canada doesn’t…”

– George Henry, COTTFN Band Council Member, Traditional Knowledge Keeper

Upon reaching Enbridge for comment, Graham White, a representative wrote in an email stating, “Enbridge is absolutely committed to fostering a strengthened relationship with the COTTFN… We will continue our efforts to engage with Indigenous communities above and beyond what is required by regulators to build trust and address any concerns or input they may have with our projects or operations.”

LISTEN: “…What we’re asking of Canadians is to be mindful of the fact that you’re in a relationship surrounded by a treaty…”

– Chief Leslee White-Eye, COTTFN

Setting a precedent

Clyde River’s case is a milestone for Nunavut, as it will be the first time the Supreme Court has ever heard a case from the territory.

When Clyde River invited Greenpeace to help them in their legal battle to fight seismic testing in July of 2014, it was a significant joining of forces, triumphing over a tumultuous history.

After Greenpeace’s anti-sealing campaign in the 1970s and 1980s, the organization did not have a good reputation in the north, explained Farrah Khan, Greenpeace’s Arctic campaigner.

Of the partnership, she said, “For Clyde River to reach out to us, is something that we definitely don’t take for granted.” Greenpeace has made the commitment to share Clyde River’s legal costs with QAA, an Inuit organization.

LISTEN: “People in Clyde River are… so courageous, and they’re seriously under threat…”

– Farrah Khan, Greenpeace Canada

Khan also said that former mayor Natanine had told her that his first reaction to the seismic project was excitement that there would be economic activity in the arctic. She explained that it was when the community started to research and understand what the project actually entailed, that initial enthusiasm was replaced with concern.

Chief White-Eye said, “We’re not about stopping development. We want to be equal players in development, but we want it to be sustainable.”

White-Eye also explained, “We’ve got, obviously, some values that are coming to a head between First Nations and corporate wants and needs, and also government’s wants and needs, and sometimes those values aren’t the same.”

Hasan summarized the significance of this case by saying that, “It’s important to work together because these are issues that affect all of us. Beyond affecting Aboriginal groups and Inuit groups, it affects all Canadians, because we all have an interest in ensuring just and fair reconciliation between the Canadian Government and First Nations that were here long before the arrival of European settlers.”