When he was younger, James Costello wouldn’t correct people who thought he was Italian. It was an assumption made often, based on his olive skin and dark hair, and on the sound of his name. His grandmother, a survivor of the residential school system, saw his lack of distinguishing Ojibwe features as a form of protection. She told him he was lucky he didn’t “look Native,” and chose not to teach him the language or customs of her youth. “I grew up denying I was Aboriginal,” James says.

When he was younger, James Costello wouldn’t correct people who thought he was Italian. It was an assumption made often, based on his olive skin and dark hair, and on the sound of his name. His grandmother, a survivor of the residential school system, saw his lack of distinguishing Ojibwe features as a form of protection. She told him he was lucky he didn’t “look Native,” and chose not to teach him the language or customs of her youth. “I grew up denying I was Aboriginal,” James says.

His name helped keep him inconspicuous: his grandmother passed on the idea that he had a “safe” name, one that “would keep me from having to go through what she went through.” But about 12 years ago, when he was 30 and wanted to reconnect with the culture he had kept at a distance for so long, seeking out his spirit name became “the first step on a healing journey” for James. He spent three weeks at a traditional healing lodge, where people go, he says, to “get healthy in all aspects.”

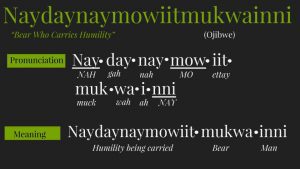

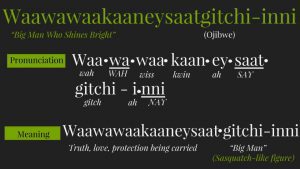

Receiving the spirit name Naydaynaymowiitmukwainni, which translates roughly to Bear Who Carries Humility, felt like a profound shift, he recalls. The change made him think about his personality and circumstances, and tied him to his history. Later on, another name came to him: Waawawaakaaneysaatgitchi-inni, or Big Man Who Shines Bright. Spirit names can turn up in many ways; through conductors at ceremonies, or in the company of family, or individually. A second spirit name doesn’t displace the first, James explains; it adds rather than replaces.

Now he works at Anishnawbe Health Toronto, where he coordinates traditional ceremonies for others to reconnect with their lost cultural practices. Naming ceremonies are among the most sought-after: James arranges two or three a day.

The erasure of Indigenous names and languages began in the 1870s. One of the tasks of “Indian agents,” the government-appointed bureaucrats who surveilled Indigenous communities in the late 19th century, was recording the names and identifying information of the people under their charge. Since assimilation was the government’s ultimate goal, these names were often written down incorrectly, either through neglect or by design. Agents sometimes substituted biblical names, or even their own. Later, many Indigenous children who retained traditional names were forbidden from speaking them in residential schools. Returning to lost traditions and ceremonies can be an important act of reclamation for Indigenous peoples, and names are often a first step.

Names are at the forefront of our identities, shaping the way we move through the world. “Our names objectify our presence as participants in interpersonal transactions, not only for others, but for ourselves as well,” wrote sociologists Darrell W. Drury and John D. McCarthy. Depriving Indigenous peoples of their wide varieties of naming practices was only one part of the campaign of forced assimilation, but it was a profoundly damaging loss, both on a broad cultural level and a very individual one. “For us, there’s power in naming,” says Lee Maracle, a course instructor and Traditional Teacher at University of Toronto. “Our names are our property.” Naming customs vary across different communities, but in the Stó:lō tradition in which Lee was raised, names are unique: they belong to only one person at a time. To be forbidden to use your name, then, is to be ordered to disregard a fundamental part of who you are.

Traditional naming practices didn’t disappear as a result of the residential school system, but the shame and the hate taught by those institutions meant that many traditions that survived carried a fraught legacy. Filmmaker and journalist Candace Maracle (no relation) grew up in Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory, in a family that had a complicated relationship to their ancestral languages. Candace is her legal name, but her mother also gave her and her sister traditional names at birth. These names function differently than their English names, Candace says: traditional names can “tell a story of our birth or the qualities of our character. It’s also how Creator knows us.” Her name, Waabigoniiskwe, means Rose Woman in old Ojibwe. It was also the name of her great-great-grandmother, a Medicine Woman. But her mother thought of Ojibwe as a language that was “almost forbidden,” Candace says, and she had instructed her daughters not to use or even speak their traditional names. Candace’s mother’s parents were both residential school survivors. Because “their language was beat out of them,” Candace says, “they passed their wounds on to their children. This is the shame my mother carried.”

Dawn Maracle didn’t grow up with a traditional name either. She’s not related to Lee, and not directly related to Candace—her last name is such a common one in Tyendinaga that her grandfather, Leonard Maracle, lived next door to another Leonard Maracle. But when Dawn started thinking about names, close to 15 years ago, she had the next generation in mind. She and her cousin had decided to trace their genealogy, and were struck by the fact that they didn’t come across a Mohawk name more recently than the 1880s. Everything since then had been anglicized. To finally see that name so many generations later “was such a poignantly powerful experience for me,” Dawn says. She decided then that if she ever had a child, she would make their Mohawk heritage a legal, traceable part of the baby’s life by including it in their name. “I want somebody seven generations down the road to be able to have a similar powerful experience and a connection,” she says.

In Mohawk tradition, not unlike the Stó:lō custom Lee Maracle described, a finite number of names are considered to be “in the basket”: thousand-year-old names belong to only one clan, in one area. Once a name is chosen, it belongs to its owner for life; only after death is it put back in the basket for someone else to use. Traditional Mohawk names also carry comprehensive and intensely specific meanings, Dawn explained: one single name is a whole sentence in English. There’s a certain gravity that comes with having a unique name; understanding that your name belongs to you alone.

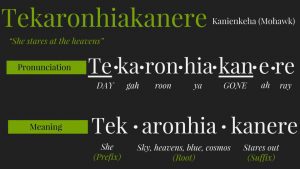

When Dawn had a baby nine years ago, she spoke with renowned Akwesasne Mohawk midwife Katsi Cook, about her experience of pregnancy, and about her dreams. In one dream her father, who had died 15 years previously, came down from the sky and presented her with a body facing upwards; the next day the kicks started. The circumstances of her daughter’s birth – “facing the sky,” Dawn says – matched those of the dream, and other considerations, including her daughter’s father’s study of astronomy, led her to the right name. Tekaronhiakanere isn’t easily translated, but the closest interpretation is “She stares at the heavens.” It included different aspects of her personality, and of her family relationships. As a baby, she would often stop crying when Dawn took her over to the window, as if reassured by the view. Her name just “really fits,” Dawn says.

As a nine-year-old, Tekaronhiakanere is sometimes frustrated to have to explain her name. She tells new people to call her Aronhia (“rhymes with petunia.”) But she recognizes how special it is to be “the only person on the planet” with her name, as Dawn puts it. They discuss the function of names often. Dawn says she hopes hopes that building their heritage into her daughter’s name will mean she will not have to “fight to learn about her family and her culture. She’s never going to go through life like I did, having to go to university to learn about who she is and where she’s from.”

For Dawn, following traditional naming practices is just “one small act,” but “it’s part of me breaking the cycle of colonialism,” she says. “It’s exactly what I’ve always wanted to do.”