Alyssa Flaherty-Spence sat in a circle with her classmates and looked at each one of them. She wasn’t staring, but it wouldn’t matter if she was.

Alyssa Flaherty-Spence sat in a circle with her classmates and looked at each one of them. She wasn’t staring, but it wouldn’t matter if she was.

As an Indigenous woman in an Aboriginal law class, Flaherty-Spence felt comfortable making eye contact with her peers and expressing her opinions about Aboriginal rights.

That was the purpose of this “talking circle”– a traditional Indigenous discussion space where one person holds a feather to talk and everyone else listens patiently. This feather is passed around the circle.

Alyssa Flaherty-Spence

Flaherty-Spence wasn’t surprised by the reactions of her classmates: students respecting her and allowing her to speak openly about issues close to her heart.

“It’s not a mandatory course and so, people are there because they want to be,” she said.

Flaherty-Spence is a third-year law student at the University of Ottawa. Recalling this incident, she says accommodating Indigenous students is slowly becoming an accepted part of law school education, but there is room for improvement.

“I appreciate my professor’s efforts in creating a comfortable space for everyone to talk. Some of the discussions were very personable and so, when holding the feather you felt more empowered.

But again, this isn’t a mandatory course in law school,” she added.

In Indigenous law studies, students are able to learn about the impact of law on Aboriginal peoples as well as hear perspectives from Aboriginal peoples on the law. Students are also educated on the history and culture.

Currently, students are required to take a first-year constitutional law course, where they may be briefly introduced to Aboriginal law.

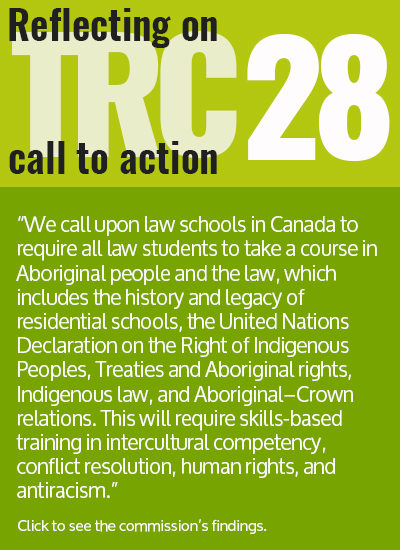

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Call to Action 28 asks all Canadian law students to take a course in Aboriginal peoples and the law, including the history and legacy of residential schools, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Treaties and Aboriginal rights, Indigenous law, and Aboriginal–Crown relations.

It also requires all students to receive skills-based training in intercultural competency, conflict resolution, human rights and anti-racism.

“I think a mandatory course that gives a broader view on Aboriginal peoples is the bare minimum.

“Aboriginal issues need to be integrated into all courses. There should be units in classes like property law focusing on Aboriginal peoples,” said Mayuran Sivagurunathan, a third-year law student at the University of Ottawa.

Meanwhile, legal educators say it’s about curriculum and altering perceptions of faculty members who teach law students.

“It’s akin to saying that once I take a first-year property course, I can now be a real estate lawyer. It’s more than that. It depends on the content and who is teaching it,” said Jeffery Hewitt, visiting scholar at Osgoode Hall Law School at York University and general counsel for Rama First Nation.

“A part of the concern may be that if there is a mandatory course then no one in the faculty will feel responsible to educate students on Indigenous issues beyond the one course,” he added.

Assistant professor at Osgoode Hall Law School, Andrée Boisselle shares Hewitt’s opinion on responsibility displacement. She also fears that mandatory education can negatively affect student engagement.

“I think the effect of trying to make people [students] who aren’t interested or are reluctant, to understand those issues and why they are relevant to everyone in one mandatory course can potentially backfire. It may just be an easy way out of the responsibility to learn about Indigenous peoples,” Boisselle said.

In addition, the call to action targets the knowledge and skills of legal professionals and highlights the deficits in lawyers both representing governments and Indigenous communities.

“In my practice, I do come across lawyers who don’t have any knowledge on Aboriginal issues,” said Lorraine Land, a lawyer at Olthuis Kleer Townshend LLP.

“A lack of background or education can actually put lawyers in situations in which they aren’t able to properly serve Aboriginal clients or they don’t have what it takes to reach an agreement with an Aboriginal community.”

Currently, Indigenous peoples make up about 4 per cent of the Canadian population and as of February 2013, 23.2 per cent of the federal inmate population was Indigenous. This disproportionate number suggests that there may be a systemic issue of racism within the justice system.

“Aboriginal peoples are much more likely to plead guilty to things that they have not done than non-Aboriginal peoples. It’s because of the mistrust between them and the justice system,” said Cathy Guirguis, a lawyer at Olthuis Kleer Townshend LLP

This relationship is what needs to change and this call to action is one of the ways that we can begin changing this.”

One part of a possible solution is addressing the history of Indigenous land and the location of Canadian law schools.

The idea is students will be better prepared to represent Indigenous Peoples and understand the history of Indigenous land claims.

Lakehead University’s law program is innovative as students are required to take mandatory Aboriginal law classes in the first year and they also receive hands-on experience working with Indigenous peoples. This program places emphasis on hiring Indigenous faculty members who can relate to the topic at hand.

“There is a course called Aboriginal Perspectives and that’s an experiential learning course. When we hire an Indigenous person for the course, the content is going to come out of their mandate.”

“I anticipate that we are really going to develop that course a lot when we are going to have an Indigenous person assigned to it. I think they will really be able to make that course special and incorporate more on Indigenous perspectives to it,” said Karen Drake, a law professor at Lakehead.

As Flaherty-Spence continues her journey to becoming a new lawyer, she is hopeful that the treatment of Indigenous peoples will change within the justice system.

“This call to action is a step in the right direction, but a lot more is required.”