Mathieu Plamondon has big goals.

Mathieu Plamondon has big goals.

The 17-year-old from Timmins, Ont. has been running races since Grade 2, winning multiple gold medals at Ontario Federation of School Athletic Associations events and North American Indigenous Games. Now, Plamondon is beginning to look to the future.

“Step by step, the first (goal) would definitely be getting a scholarship,” said Plamondon. “After that would be a NCAA title and then possibly going pro. The ultimate one would obviously be going to the Olympics and running for Canada.”

Plamondon doesn’t have any athletes in his immediate family, a family whose ancestry goes back to the Grassy Narrows First Nation. He is one of the few Ojibwe individuals in his community. “Everyone around here is mostly Cree,” said Plamondon.

Becoming an elite athlete is not easy, but Plamondon has positioned himself to become one. But, for a variety of reasons, making it to the highest level of sport is not something many Aboriginal peoples are able to do.

TRC brings focus to sport

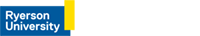

In the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action, points 87-91 all focused on improving Aboriginal sport. Call 88 specifically stated a need for governments to ensure there is a long-term athlete development model in place for Aboriginal Canadians.

“I think the (TRC’s) point about sport is it touches on systemic inequality by saying, ‘look, you need to put money towards the development of Aboriginal sport,’” said Janice Forsyth, a former Indigenous Games participant. “And I would even go a step further and say Sport Canada needs to support funding for Aboriginal sport while easing up on their criteria for funding.”

Forsyth is currently an assistant professor and former director of the International Centre for Olympic Studies in the Faculty of Health Sciences at Western University. She has written about Aboriginal sport issues for a variety of publications and co-edited the book Aboriginal Peoples & Sport in Canada: Historical Foundations and Contemporary Issues in 2013.

The way sport organizations are funded in Canada is a common issue. Funding often goes to the groups who can win the most medals rather than investing in ones who may need assistance just to stay afloat. The cost of sport itself is also a problem – especially in many Aboriginal communities.

“Elite sport is a privileged playground for the upper middle class,” said Forsyth. “So it’s usually going to be the privileged kids who can afford to stay in the system in order to make it that far. Poverty is a huge factor. There’s also racism. It’s an unwelcoming space.”

Even in the value of sport in Aboriginal communities is a topic for discussion, said Forsyth.

“If we’re talking about what is it that Aboriginal communities are struggling with its environmental concerns, legal issues – like treaties and medical concerns – and the retainment of their culture. I think performing in sport kind of falls somewhere far down the list.”

In Forsyth’s book, there is a chapter on the challenges facing elite Canadian Aboriginal athletes. One of the major issues is the fact many will have to leave their communities to continue climbing the sport development pathway. This often creates a culture shock – the different coaching structure, being viewed as an outsider, the lack of a family support system and even a different diet can all play a role in negatively affecting development.

Forsyth has seen these issues first hand, where an Aboriginal athlete wasn’t named to a national team roster because the coach was concerned he would be unable to adapt and head home.

The sport pathway

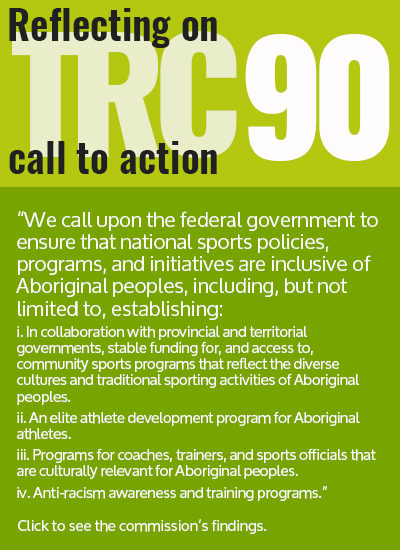

There are many organizations trying to fix these problems. At the national level, Canada Sport for Life and the Aboriginal Sport Circle created the Aboriginal Long-Term Participant Development Pathway this past January. A press release stated that the pathway, which maps out an athlete’s start in sport and how they can eventually reach the elite level, is “a culturally sensitive resource that directly speaks to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report: Calls to Action around sport and physical activity.” Many provincial sport organizations, like the Aboriginal Sport & Wellness Council of Ontario (ASWCO), organize and deliver programs that assist in athlete development. The ASWCO organizes provincial championships, delivers coaching workshops and provides grants communities can apply for.

Many provincial sport organizations, like the Aboriginal Sport & Wellness Council of Ontario (ASWCO), organize and deliver programs that assist in athlete development. The ASWCO organizes provincial championships, delivers coaching workshops and provides grants communities can apply for.

The value of the NAIG

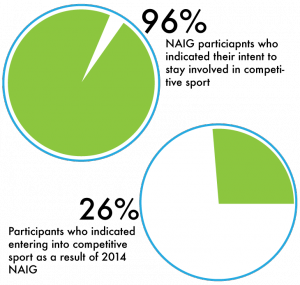

The North American Indigenous Games – affectionately referred to as the NAIG (pronounced “nag”) – is also a critical part of sport development, said Forsyth.

“(The NAIG) provides that space where Aboriginal athletes can go and be with other Aboriginal athletes in what is very close to a high performance environment. It gives them all that sense of accomplishment, that self-esteem and the experience of a big multi-sport venue. It’s that stepping stone to a higher level of competitive development but at the same time if that is not their aspiration – if the NAIG is it – then it’s it.”

The Games have been held intermittently since 1990. While several different Canadian cities have hosted since then, the NAIG has never been held east of Winnipeg. That will change in 2017.

Rob Lackie was one of the bid committee members and is currently the operations manager for the 2017 Games, which will be held in Toronto next summer. After no US cities were able to organize a bid, Ontario was awarded the event last year.

“We stepped up this time to make sure there wouldn’t be that six-year gap between the 2014 games and the 2020 games – because that’s just too long,” said Lackie.

The 2014 NAIG was held in Regina and featured 14 sports for male and female athletes between the ages of 14 and 19. Lackie expects there to be around 5,000 athletes at the 2017 event and roughly 20,000 spectators. A key component of Toronto’s successful bid was the Pan Am Games facilities, which will play host to most of the events.

The 2014 NAIG was held in Regina and featured 14 sports for male and female athletes between the ages of 14 and 19. Lackie expects there to be around 5,000 athletes at the 2017 event and roughly 20,000 spectators. A key component of Toronto’s successful bid was the Pan Am Games facilities, which will play host to most of the events.

The Pan Am Games left a legacy in Ontario in the form of infrastructure and inspiration. Lackie hopes the NAIG can leave a legacy on the Aboriginal sports community in the province.

“The big part of it is the training,” said Lackie. “(The ASWCO has) created some new programs – we call them Aboriginal coaching modules – and that gives a specific sport training to potential trainers and coaches.”

Plamondon participated in the 2014 NAIG and said it was “by far the most fun event” he had participated in. He’s eligible for the 2017 Games as well and could inspire future athletes.

“I hope to be able to influence a lot of younger athletes that are Aboriginal to continue to do what they love and try and make the best out of it,” said Plamondon.